“When I was going to school… I could go read what Aristotle wrote… the problem was: you can’t ask Aristotle a question… As we look towards the next 50 to 100 years, if we really can come up with these machines that can capture an underlying spirit or an underlying set of principles or an underlying way of looking at the world, then when the next Aristotle comes around, maybe if he carries around one of these machines with him his whole life - his or her whole life - and types in all this stuff, then maybe someday after the person's dead and gone, we can ask this machine, ‘hey, what would Aristotle have said’?”

These days, we are all carrying “one of these machines” in our pockets, and they are capable of recording every action we take and every word we utter, so you would think this reality is around the corner: that we could soon interact with digital versions of the next Aristotle, its AI-twins, and have an infinite number of such Aristotle’s at our disposal. Perhaps soon we could also get access to Ricardo-Muti’s AI-twins to ask about classical music, and get tennis tips from Federer’s AI-twins. At work, we could reach out to the AI-twins of any colleague at work and have them answer our pressing questions, without having to book a meeting. On a more personal level, our own grand and great-grand-children could get access to our AI-twins, strengthening our intergenerational bonds for decades to come. Wouldn’t we all like to have been able to probe the minds of our ancestors?

The technology for creating such AI-twins is not too far off. As a case in point, last year, Reid Hoffman (founder of LinkedIn) created an AI version of himself by training an AI model on his writings and speeches in both text and video, and Reid then went on to have an in-depth conversation with this AI-twin, who (sic!) answered his questions quite competently and even used similar gestures and nuances as the real Reid.

Today many tech companies are trying to figure out the right approach to this idea, experimenting to find successful solutions, balancing social norms and expectations, and probing the boundaries of confidentiality and appropriateness. Still, chances are that it will take a little more time for them to find the right magic formula, and so we will not get a whole bunch of AI-twins unleashed out into the world overnight. Rather, these will likely be built step by step over time.

We may see the fastest progress in the corporate world, where the productivity gains from such AI-twins are expected to be immense. We are already seeing AI assistants draft emails for us, and suggest responses to emails we receive, asking us to confirm their draft answer, to just press “Accept” and send. If a colleague asks you a question over email, we could imagine that these AI-Assistants will be able to read your old emails and try to find the right answer. Your company might also give them access to your documents and your Slack messages, so that the AI-Assistant can try to find the right answers, accumulating the knowledge bit by bit, and suggest increasingly better answers. You would just need to review and “Accept”. Admittedly, at that point, we would still be far from a Reid-Hoffman-like AI-twin, and probably still have to draft many an email ourselves. We might even get frustrated at the lack of progress and mock the AI’s intelligence(!) when it makes mistakes. We would probably clamor for better solutions. Well, one thing the industry has learnt is that the sure way to improve AI is to feed it more data. So, perhaps we can ask the AI Assistant to start listening to our Zoom calls and Teams meetings and phone conversations to train itself, in the same way that Reid’s AI -twin trained on recordings of his talks. As the AI assistant absorbs more and more of our interactions and video conversations, it will certainly improve, gathering the latest data and emulating our idiosyncrasies. Soon we would be able to trust the AI to respond on our behalf in our style with our nuances for each correspondent, and we may not even have to check the answers, or press “accept” – Just let this new AI-Agent work for you.. to represent you, in both senses of the word. At that point, it would be safe to say that this AI-Agent would truly be a reflection of you, a shadow of your identity that will only get sharper as it trains on more data. To use Jobs’ words from 1983, it may “capture an underlying spirit”, a sense of your self or your soul, at least your corporate soul.

What about your non-corporate identity - your real soul? If we are to have AI-twins that can act as agents and represent us, taking actions on our behalf, and even talk to our grand children one day, we will have to train it on more and more of our personal data too. However, under the structure of the internet, as it stands today, we have largely delegated control of that personal data to internet giants like facebook and Google. We have struck a faustian bargain where we enjoy free services on these sites in exchange for providing our data to them. This has not been such a bad bargain for us until now. After all, our data is only being used as cannon fodder for giant advertising machines – something that may seem creepy at times – but has rarely done most of us any harm. Now, if our data starts to be accumulated to be formed into our digital twins, would we want that same bargain to stand? When we will be asked to give an AI model access to that incremental piece of personal data on us so that it can draft a better email for us, or better plan that proverbial customised holiday for us, will we just press “accept”? Will we strike the same bargain knowing that with each bit of data, our digital representation will improve, the shadow of our self becoming slightly sharper, all the while imprisoned within the cave-like computer data centers of these tech giants? Would we want a Facebook or an OpenAI to control our digital twins, to mediate our future conversations with our grandchildren for example, and to be able to censor that conversation, or even bestow it with super-intelligent math skills, or to delete our data as it sees fit.. to destroy our AI-twin at its whim?

Following the Scientific Revolution, Enlightenment philosophers like Locke and Rousseau worked to rethink the nature of human beings, and to re-imagine our social contract with society and government. Similarly today, as we start to understand the power and implications of our own data traces, knowing they can be used to create such true representations of our selfs, knowing that they could go on to live forever and to evolve in their digital forms even without us, we will need to rethink the nature of that data and the nature of the personas that may be built with it, and we need to re-imagine the ideal relationship these personas should have with us, with society and with the owners of the computers on which they reside.

Perhaps if we could conjure Rousseau’s own AI-twin, he would proclaim that today: “our data is born free, yet everywhere it is in chains.” Just as the real Rousseau pointed to the origin of private property as a starting point for the inequities he saw in society, his AI-twin might think of the origins of our current predicament and point to the first clickable online advertisement sold in 1994, and the consumer profiles that advertisers would then seek to build using the traces of our online activity. And just as Rousseau and his cohort of Enlightenment philosophers helped build a new foundation for society by defining the Nature of humanity, and what it means for humans to be free and autonomous, perhaps we will need to think about the Nature of our data, what it might mean for our data to be free and autonomous, and re-imagine the principles upon which a data-rich society should be governed – a new social data contract.

----

PS And what of Homer’s AI-twin? Indeed it is always important to heed the advice of the ever-clairvoyant Simpsons.

This is the second in a series of posts that contemplate some existential questions emanating from AI. While the previous post related to the nature of humanity, this one relates to the nature of AI itself.

To-date, AI models like ChatGPT have been largely trained on publicly accessible data that us humans have inputted onto the public domain, on web sites like Reddit or Wikipedia, thoughtlessly exposing ourselves and our humanity, unaware that our words, and all the creativity, knowledge, passion and prejudice they contain, might one day help train an AI model. As such, at their core, the current generation of AI models are reflections of humanity, innocently exposed.1

Of course, some of that innocence has already been lost. Before these models are exposed in the interfaces we consumers see on sites like ChatGPT, they typically go through a series of adaptations or trainings. These trainings can range from simple guidelines that are added to each user request to give the AI more direction, to third party human training (where humans can compare two answers generated by the AI and tell it which one is more correct, thus guiding the model’s choices for future answers) to complex automated reward algorithms. It is thanks to this kind of training that a ChatGPT can provide such coherent answers, but also refuse to show us how to build a nuclear weapon…. and also why a China-based AI model might not discuss Tiananmen Square or Winnie the Poo. In each case, the output of the models are influenced and guided by the specific intents of their creators, and the moral values they embed in the models.

Sometimes those values can surface in unexpected ways. A famous example was the image generator model from Google which showed images of African Americans when it was asked to create a picture of the American founding fathers, thus betraying the diversity guidelines Google had imbued the model with. Some people, like Elon Musk, point to incidents like the Google mishap, arguing that AI models should only seek the truth, rather than be provided with value judgements such as diversity guidelines. However, not providing any moral guidelines is itself a value judgement, a statement that the model should not correct for the prejudices, errors and misconceptions of the past. What’s more, as AI models become more agentic and more pervasive in our lives, as they assume a greater role in taking actions or making decisions on our behalf, they will inevitably face situations where they would have to make value judgements, and they will inevitably use their training to do so, whether these values have been implicitly present in their core training data, or explicitly added by the model’s creators.

We can use an example from self-driving cars as a thought experiment. Self-driving cars are a good way to think about agentic AI, first because they already exist and so we can more easily relate to them (as opposed to potential future AI use cases we can only speculate about); and second because self-driving cars do act much in the same way that the industry is imagining AI agents will work in the future. That is, humans set a goal for the AI (like asking a car to drive to a certain address) and the agent (which, in this case has a vehicle form-factor) needs to make a series of decisions to get us to our goal – finding a route, stopping at red lights, avoiding collisions etc.

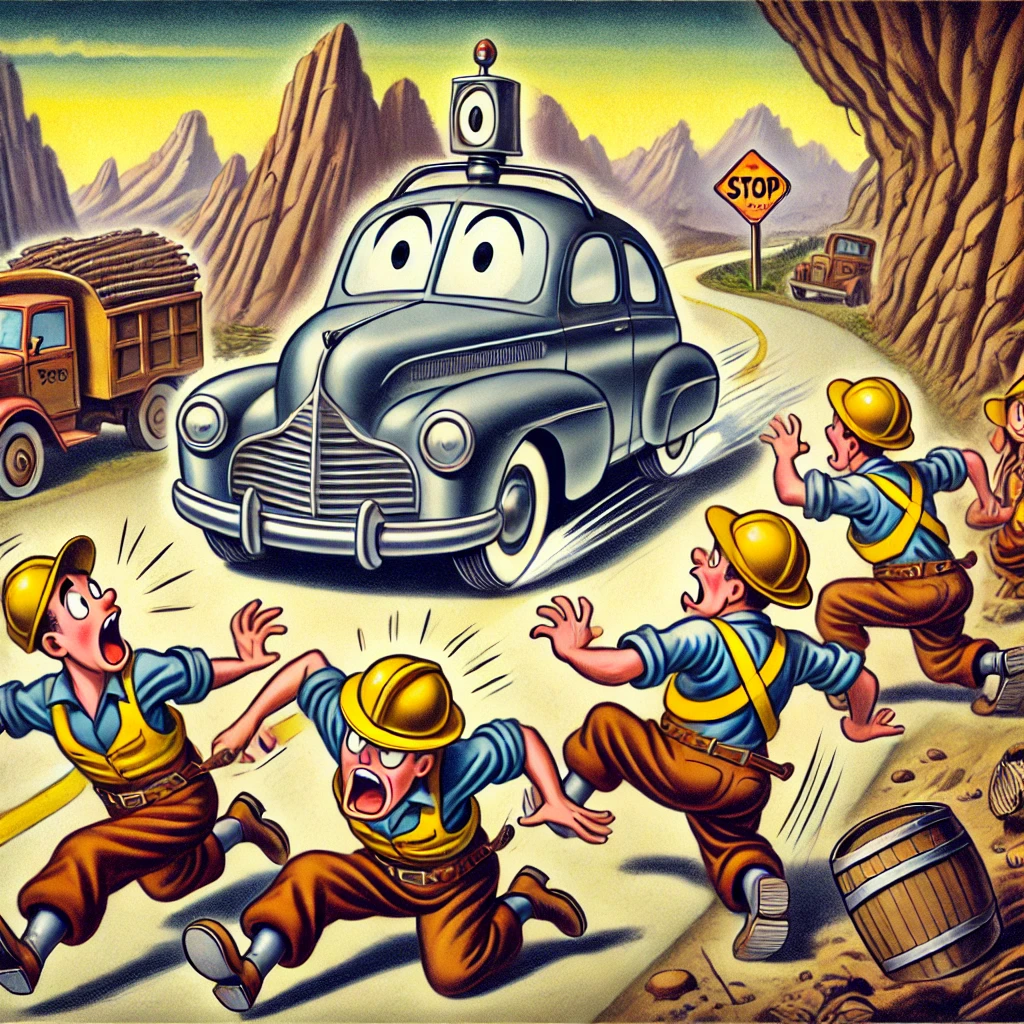

Now, let’s apply the trolley problem to self-driving cars. (The trolley problem refers to the situation where a runaway train trolley is on track to kill 5 people, but a bystander can pull a lever to force the train on another track and kill only 1. If the bystander neglects the problem, 5 will die, and by taking explicit action and pulling the lever, only one would be killed.)

Imagine a car on a mountain road that makes a tight turn and to its surprise, finds 5 construction workers right in front of it. If the car continues on its path, it will kill all 5. If it turns to avoid them, it will fall off a cliff and kill its own passenger. If the driver was human – (s)he might come out of car crying at the tragedy, and state in all honesty that (s)he acted on instincts or didn’t have time to think, or didn’t see the people, and that it all went too fast – even if (s)he made a conscious decision to turn or not to turn, it’s quite possible that the memory of such a decision would be suppressed by the trauma of the aftermath. But if an AI computer was the driver, it would have the cameras to see everything and it would have the computing power and speed to process the data and it would have to make an explicit and well-informed decision to turn or not to turn, without any excuses about “instincts” or not having “time to react”. What’s more, the computer would probably save all the input and output data points, and all of those could be retrieved later and examined in detail. A paradise lost indeed!

The one excuse we could imagine the AI would make is something like: “it wasn’t me – it was my input data!!” This brings us back to the model creator - the self-driving car company, which might want to deny all responsibility and state that the AI’s decision making takes place in a “black box” and claim that it is hard to know how the AI would come up with such a decision. We hear this kind of reasoning even today. Yet if we accept that each model is trained (or can be trained) with some implicit and explicit set of moral values and truths, as posited above, then the self-driving car’s decision to turn or not to turn would be the consequence of those same values and the direction given by the model creator. This creates an uncomfortable situation for all AI model creators. If they explicitly train the model on that specific question, the decision will become their direct responsibility. If the model is trained with a utilitarian outlook, and is optimized to maximize societal good, then the car would turn and kill its own passenger. If the model is trained to prioritize safeguarding the life of its passengers above all else, then it would certainly kill the other 5. And if the model creator turns a blind eye to all such value judgements and neglects to train the model to make such difficult decisions, then it would be guilty of gross negligence. Any of these choices, heretofore left within the mysterious depths of the drivers’ brains, suddenly enter the very uncomfortable realm of the explicit – they become a direct result of the training decisions taken by the model creators, fully verifiable and replicable.

Over the past few decades, the ethical and philosophical implications of the trolley problem have animated many a collegial debate in philosophy-101 classes, without a need for urgency or any final resolve. Now suddenly the problem becomes both existential and urgent.

Until now, if an AI system got something woefully wrong, it could be considered cute or it may create an innocuous little scandal on social media, but no one would have died from some inappropriate image generated by the AI, or gone bankrupt from it. In the future, as AI takes on more and more agentic actions, and as it is asked to perform tasks on our behalf in this newly self-driving internet, it will certainly run into digital versions of the trolley problem on its way, and it will be forced to make decisions in very uncertain circumstances. It will face problems and questions that it has not been specifically trained on, and where it would have to draw on the core set of values embedded within it to decide on a best course of action. This will (or at least should) force those values to have to be stated explicitly. In other words, the model would have to be trained on specific moral reasoning. And so, the philosophical questions underpinning its choices will have to emerge from the theoretical and enter the realm of the practical, being transformed from innocuous philosophical questions in ivory towers to urgent existential conundrums for society as a whole.

__________________

Footnotes

Image generated by openai

1. An analogy could be made to the state of world wide web before Google, when people innocently created links to other web pages, unaware that Google’s new Page Rank algorithm would use these same links to rank web sites – a paradise lost, after which all links were burdened with the knowledge of their contribution to PageRank.

… and other Existential Questions in the age of AI

In the 16th Century, the Scientific Revolution and new technologies such as the telescope allowed us to dispel the theory of earth-centrism - the belief that the earth is at the center of the universe and that it is unique in that way. It took overwhelming scientific evidence and much tumult for modern beings to mostly accept that our solar system lies in a non-unique part of a vast universe, rather than at the epicenter of a god-created one. Even so, still today, the most atheist among us have an innate sense in the validity of the theory of human-exceptionalism - that there is something special about us human beings nonetheless - that there is a soul of sorts that makes us humans unique, and which goes beyond the scientifically understood biochemical reactions within our brains. Will AI dispel that belief? Sam Altman, @sama, one of the people who is closest to the cutting-edge developments in AI, seems to believe so. Already back in 2016, he said “There’s absolutely no reason to believe that in about thirteen years we won’t have hardware capable of replicating my brain… When I realized that intelligence can be simulated, I let the idea of our uniqueness go, and it wasn’t as traumatic as I thought.”

The logical follow-up question is: if a perfect replica of Sam Altman’s brain could be created, would that be considered a human being? And the answer, so obvious to all of us, would of course be NO.

Now let us imagine that, God forbid (!), that Sam has an accident and is irreparably paralyzed, but that his brain continues to function. Certainly, modern technology would allow us to connect computers to his brain and translate brain signals into language so that we can continue communicating with him. Certainly, most of us would consider him human at that point. For example, we may all agree that he should be allowed to vote. Now, as a registered organ donor, he may also dispense of some of his other body parts, for which he would no longer have any use… ultimately being left with only the minimal organs needed to keep his brain functioning. Then, as time wears away at some of his brain cells and erodes his memory, perhaps, given that we already have a computer hooked up to him, we can have his brain read some of his memories from a computer. Over time, as technology progresses, we will surely have opportunities to substitute more and more of his brain with a computer version. At what point does he stop being a human being? At what point should he not be allowed to vote?

Philosophers through the ages pondered this same type of question with respect to the ship of Theseus (wondering if a ship which has all its planks renovated one by one can be considered the same ship.) But for them, this question was only of theoretical interest - there was no existential urgency to finding the answer. In the case of Sam’s brain though, as science progresses and enables computers to substitute and replicate more and more of our uniquely human traits, questions about the nature of humanity will yet again become both existential and urgent.

_____________________________

image generated by openai

Me: Write a blog post comparing chatGPT to ETFs

ChatGPT and ETFs are two very different things, so it's difficult to compare them directly. However, both are interesting in their own ways, and understanding the differences between them can be helpful in understanding how each can be used.

[.. the rest of ChatGPT's answer read like an 7th grader's essay... so I thought to explain further... ]

Yes, that makes sense. ChatGPT is a large language model trained by OpenAI, which means that it has been trained on a huge amount of data and can generate text that sounds like it was written by a human. However, it is not capable of creating new knowledge or making unique insights. It can only generate text based on the knowledge it has been trained on.

Similarly, ETFs are based on the systemic knowledge of the market as a whole. Buying a market ETF will give you exposure to the overall market, but it won't allow you to make unique bets or take advantage of mispriced securities. It will simply track the performance of the market index or basket of assets that the ETF is based on.

However, both ChatGPT and ETFs can be used as a starting point for human ingenuity and talent. In the case of ChatGPT, a person can use the generated text as a starting point and then focus on improving it and adding their own unique insights. With ETFs, a person can use the market knowledge provided by the ETF as a starting point and then focus on identifying mispriced securities and making bets on them in order to potentially outperform the market. In both cases, human ingenuity and talent can be used to build on the systemic knowledge provided by ChatGPT or ETFs in order to create something new and unique.

In his widely-read post on web3 , Moxie Marlinspike re-iterates over and over again that “If there’s one thing I hope we’ve learned about the world, it’s that people do not want to run their own servers.” The image he seems to have in mind is of a big old-style PC with a cd-drive sitting under the messy desk of a nerd, who spends his(!) time making sure it is running smoothly. So of course, seen in that way, as Moxie notes, “Even nerds do not want to run their own servers at this point.” But then he goes on to say that “Even organizations building software full time do not want to run their own servers at this point.” And therein lies his logical flaw. All these “organizations building software” do have their own servers – except that the servers are running in the cloud – some are even called ‘serverless’. Of course individuals don’t want to maintain physical personal servers sitting under their desks, but, much like those software organizations, we may all very well want to have our own personal servers in the cloud, if these were easy enough to install and maintain, and if we had a rich eco-system of apps running on them.

This has been an ideal since the beginnings of web1, when, as Moxie himself says, we believed “that everyone on the internet would be both a publisher and consumer of content as well as a publisher and consumer of infrastructure” – effectively implying that we each have our own personal servers and control our data environment. Moxie says it is too “simplistic” to think that such an ideal is still attainable. Many web3 enthusiasts believe web3 can provide the answer. My view is that (regardless of the number we put in front of it), at some point, technology and technology mores will have advanced far enough to make such a personal server ecosystem feasible. We may be close to that point today.

But before laying out my reasoning, let me present two other minor critiques of Moxie’s excellent article.

First is the way in which Moxie criticizes what he calls “protocols”, as being too slow compared to “platforms”. Although he may be right in the specific examples he notes – i.e. that private-company-led initiatives from the likes of Slack and WhatsApp have been able to move so much faster than standard open ‘protocols’ such as IRC – he makes this argument in a general context of web2 vs web3, and thus seems to imply that ALL open community-led projects will fail because private-led initiatives will inevitably innovate faster. But how could such a statement be reconciled with something like Linux, the quintessential open source project which is the most used operating system to access the web and to run web servers? How can one not think of html and the web itself, and javascript, each of which are open platforms, or simple agreed-upon conventions – upon which so much innovation has been created over the past decades? In defense of Moxie’s point, if you talk to anyone involved in the development of these over the years, chances are that they will complain about how slow moving their respective technical committees can be. But perhaps that is how fundamental tech building blocks should be – it is precisely the slow-moving (and arguably even technologically under-innovative) nature of platforms and protocols that provides the stability needed for fast-moving innovators to build on them. The critical societal question isn’t whether a particular protocol or web3 initiative will be innovative in and of itself, but whether any one or multiple such initiatives will serve as a foundation upon which multiple fast-moving innovations can be built, preferably using an architecture which supports a healthy ecosystem. The base elements (or ‘protocols’) don’t necessarily need to be fast moving themselves – they just need to have the right architecture to induce innovations on top of them.

In this light, as Azeem Azhar has noted, a couple of the more interesting web3 initiatives are those that are trying to use crypto-currency-based compensation schemes to create a market mechanism for services, thus tackling problems that web2 companies had previously failed to solve. One example is Helium, which is a network of wifi hotspots, and another is Ethereum Swarm, which is creating a distributed personal storage system. Both of these ideas had been tried a decade or two ago but never gained the expected popularity, and they are now being reborn with a web3 foundation and incentive system. Indeed, as it tends to, technology may have advanced far enough today to make them successful.

My last critique of Moxie’s article is that he contends that any web2 interface to web3 infrastructure will inevitably lead to immense power concentration for the web2 service provider, due to the winner-takes-all nature of web2. I would contend that it does not need to be that way, and we can point to the cloud infrastructure services market as evidence. This may be seem like a counter-intuitive example, given the dominance of big-tech and especially Amazon’s AWS of the cloud infrastructure market, but the dynamics of this market are vastly different from the b2c markets that are dominated by the same big-tech companies (Google, Amazon, and Microsoft). Despite every effort by these big-tech usual suspects to try and provide proprietary add-ons to their cloud services so as to lock in their customers, they are ultimately offering services on a core open-source tech stack. This means that they are competing on a relatively level playing field to offer their services, knowing that each of the thousands of businesses that have thrived on their infrastructure can get up and leave to a competing cloud provider. The customers are not locked in by the network effects that are typically seen in b2c offerings. That is clear from the rich ecosystem of companies that have thrived on these platforms. Furthermore, not only can competitors in the cloud infrastructure market take on various niche portions of this giant market, but new entrants like Cloudflare and Scaleway can also contemplate competing head-on.. This competition, which is enabled by the existence of a core open-source tech stack, keeps even the most dominant service providers honest(!) as their customers continue to be king. There is no better evidence for that than the vibrancy of the ecosystems built on top of these services, and in stark contrast to the consumer world where the lack of interoperability and the strength of the lock-ins provide immense barriers to entry. Given a similar architecture, there is no reason these same dynamics can’t be transposed to the personal server space and the b2c market.

Yet, by going in with the assumption that such a thing is impossible, Moxie misses the opportunity to think through what new architectural solutions are possible by combining web3 elements with our existing technological interactions, and whether such new architectures could enable strong enough competition and portability, to curb the winner takes-all dynamics of the current b2c consumer web services market.

This brings us back to my pet peeve of personal servers – a concept that has been around for more than a decade, and that the tech world has come to believe will never work. The question is: have recent developments in tech fundamentally shifted the landscape to make the original ideal of web1 viable again. My view is that the stars may be finally lining up, and that such an architecture is indeed possible.

✨ Web 3

A first star may be the launch of Ethereum Swarm, “a system of peer-to-peer networked nodes that create a decentralised storage”. As mentioned, Swarm uses Ethereum smart contracts as a basis of an incentive system for node participants to store data. It is quintessentially web3. Yet, it acts as a core infrastructure layer, on which anything can be built. So, the Fair Data Society, a related organization, built fairdrive, a web2 based gateway to access this storage infrastructure – a key building block for allowing other web2 based applications on top of it. Moxie’s blog post would argue that any such web2 interface would reconcentrate power in the hands of the same web2 service provider. But that really depends on what is built within and on top of that gateway – the architecture that lays on top of the foundational storage. If the data stored is in an easily readable format, based on non-proprietary and commonly used standards; and if there are multiple competing gateways to access this data, allowing anyone to switch providers within a minute or two, then there is no reason for those web2 interface service providers to be able to concentrate undue power.

So how could these two elements come together – the data format and the portability / switch-ability?

🤩 Web 2 Switch-ability

As mentioned above, the competition among b2b cloud infrastructure providers has continued to allow for immense value to accrue to their customers. Until now, these customers have been other businesses that use the cloud. Even so, the cloud providers have done such a good job providing better and better solutions for these customers, which are ever easier to deploy, that such solutions have become almost easy enough to be also deployed for consumers. So not only can one easily envisage a world where multiple service providers compete by providing the best possible personal cloud services to consumers, one does not even need to wait for that. Today, it takes just a few clicks to create a new server on Heroku or on glitch.com or a myriad of other services. Anyone can easily set up their own server within a few minutes. This bodes well for a leading edge of tech-savvy consumers to do exactly that!

But then what? What would you put on those servers? What data, and in what format? How can you make sure that such data is compatible across server types, and that such servers are interoperable (and switch-able), wherever they may sit?

💫 Web1 and the Personal Server Stack

A first step towards such interoperability is the CEPS initiative, which came out of the 2019 mydata.org conference and aimed to define a set of Common Endpoints for Personal Servers and datastores so that the same app can communicate to different types of personal servers using the same url endpoints. (ie the app only needs to know the base url of each user’s server to communicate with it, rather than create a new API for every server type.) With CEPS, any app developer can store a person’s app data on that person’s personal storage space, as long as the storage space has a CEPS compatible interface. CEPS also starts to define how different CEPS-compatible servers can share data with each other, for example to send a message, or to give access to a piece of data, or to publish something and make it publicly accessible. This data, “users’ data” – sitting on their personal servers is assumed to be stored in nosql data tables associated with each app. And whether the data is sitting in flat files or a cloud-based data base, it can easily be downloaded by its owner and moved somewhere else without losing its cohesiveness. This ensures that ‘user-data’ is indeed easily portable and so the ‘user’ or ‘data-owner’ can easily switch services – ie that the service provider doesn’t have a lock-in on the data-owner.

A second step would be to also store the apps themselves on the personal data space. Code is data after all, and so, having our apps be served from other persons’ servers seems incompatible with the aim of controlling our own data environments. It would leave too much room for app providers to gain the kind of power Moxie has warned us against. These apps, like one’s data, also need to be in a readable format and transportable across servers and mediums. Luckily, since the advent of web1, we have all been using such apps on a daily basis – these are the html, css and javascript text files that together make up each and every web page. Instead of having the app-providers host these files, these files can also be stored on each person’s personal storage space and served from there. Then each data-owner would have control over their data, as well as the app itself. The use of such an old standard not only ensures easy portability of the apps, but it also means that thousands of developers, even novices, would be able to build apps for this environment, or to convert their existing web-apps to work in that environment. It also implies that the server-layer itself plays a very small role, and has less of an opportunity to exert its dominance.

I started this essay by claiming that people “may very well want to have their own personal servers in the cloud, if these were easy enough to install and maintain, and if they had a rich eco-system of apps running on them.” I have tried to depict an environment which may have a chance of meeting this criteria. If we start by converting our existing web-apps to this architecture, we may be able to use the web3 foundation of Swarm to forge a path towards the web1 ideals of controlling our web environment and data, all with the ease-of-use and the ease-of-development which we have gotten used to from web2.

🌹 Any Other Name

So then, the only problem remaining would be the name ‘Personal Server’… because Moxie may be right on that too: after all these years of false starts, it has become such a truism that no one would ever want a ‘personal server’, that the term itself may be too tainted now for anyone to want to run one.. so perhaps we should just rename ‘personal servers’ to “Serverless Application Platforms”.

____________________

Note: freezr is my own implementation of a personal server (ahem.. Serverless Application Platform), consistent with the architecture laid out above.

I will giving a demo of freezr at the We are Millions hackathon on March 10th.

I modified NeDB for freezr so it can use async storage mediums, like AWS S3 and or personal storage spaces like dropbox. The code is on github, and npmjs.

Each new storage system can have a js file that emulates the 16 or so functions required to integrate that storage system into nedb-asyncfs. A number of examples (like dbfs_aws.js) are provided under the env folder on github. Then, to initiate the db, you call the file as such:

const CustomFS = require('../path/to/dbfs_EXAMPLE.js')

const db = new Datastore({ dbFileName, customFS: new CustomFS(fsParams)})

where dbFileName is the name of the db, and fsParams are the specific credentials that the storage system requires. For example, for aws, fsParams could equal:

secretAccessKey: '22_secret22'

To make this work, I moved all the file system operations out of storage.js and persistence.js to dbfs_EXAMPLE.js (defaulting to dbfs_local.js which replicates the original nedb functionality), and made two main (interrelated) conceptual changes to the NeDB code:

1. appendfile - This is a critical part of NeDB but the function doesn't exist on cloud storage APIs, so the only way to 'append' a new record would be to download the whole db file and then add the new record to the file and then re-write the whole thing to storage. Doing that on every db update is obviously hugely inefficient. So instead, I did something a little different: Instead of appending a new record to the end of the db file (eg 'testdb.db'), for every new record, I create a small file with that one record and write it to a folder (called '~testdb.db', following the NeDB naming convention of using ~). This makes the write operation acceptably fast, and I think it provides good redundancy. Afterwards, when a db file is crashsafe-written, all the small record-files in the folder are removed. Similarly, loading a database entails reading the main dbname file plus all the little files in the ~testdb.db folder, and then appending all the records to the main file in the order of the time they were written.

2. doNotPersistOnLoad - it also turns out that persisting a database takes a long time, so it is quite annoying to persist every time you load the db, since it slows down the loading process considerably... So I added a donotperistOnLoad option. By default the behaviour is like NeDB now, but in practice you would only want to manage persisting the db at the application level... eg it makes more sense to have the application call 'persistence.compactDatafile()' when the server is less busy.

Of course, latency is an issue in general, and for example, I had to add a bunch of setTimeOuts to the tests for them to work... mostly because deleting files (specially multiple files, can take a bit of time, so reading the db right after deleting the 'record files' doesnt work. and I also increased the timeout on the tests. Still, with a few exceptions below, all the tests passed for s3, google Drive and dropbox. Some notes on the testing:

- testThrowInCallback' and 'testRightOrder' fail and I couldnt figure out what the issue is with it. They even fail when dbfs_local is used. I commented out those tests and noted 'TEST REMOVED'

- ‘TTL indexes can expire multiple documents and only what needs to be expired’ was also removed => TOO MANY TIMING ISSUES

- I also removed (and marked) 3 tests in persistence.test.js as the tests didn't make sense for async I believe.

- I also added a few fs tests to test different file systems.

- To run tests with new file systems, you can add the dbfs_example.js file under the env folder, add a file called '.example_credentials.js' with the required credentials and finally adjust the params.js file to detect and use those credentials.

I made one other general change to the functionality: I don't think empty lines should be viewed as errors. In the regular NeDB, empty lines are considered errors but the corruptItems count starts at -1. I thought it was better to not count empty lines as errors, but start the corruptItems count at 0. (See persistence.js) So I added a line to persisence to ignore lines that are just '/n'

Finally, nedb-asyncfs also updates the dependencies. underscore is updated to the latest version, as the latest under nedb had some vulnerabilities. I also moved binary-search-tree inside the nedb code base, which is admittedly ugly but works. (binary-search-tree was created by Louis Chariot for nedb, and the alternative would have been to also fork and publish that as well.)

vulog is a chrome extension that allows you to (1) bookmark web pages, highlight text on those pages, and take notes, (2) save your browsing history, and (3) see the cookies tracking you on various web sites (and delete them).

I wrote the first version of vulog 3 years ago to keep a log of all my web pages. It seemed to me that all the large tech companies were keeping track of my browsing history, and the only person who didn't have a full log was me! I wanted my browsing history sitting on my own personal server so that I can retain it for myself and do what I want with it.

At the time, I had also added some basic bookmarking functions on vulog, but I have been wanting to extend those features and make them much more useful:

- Keyboard only - Most extensions are accessed via a button next to the browser url bar. I wanted to make it faster and easier to add bookmarks and notes by using the keyboard alone. So now you can do that by pressing 'cntrl s', or 'cmd s' on a mac. (Who uses 'cntrl s' to save copies of web pages these days anyways? )

- Highlighting - I wanted to be able to highlight text and save those highlights. This can now be done by right clicking on highlighted text (thanks to Jérôme).

- inbox - I wanted to have a special bookmark called 'inbox' and to add items to that inbox by right clicking on any link.

So these are all now implemented in the new vulog here:

https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/vulog-logger-bookmarker-h/peoooghegmfpgpafglhhibeeeeggmfhb

The code is all on github.

This post is supposed to be a live document with the following sections:

1. Known Issues

Here are some known problems and deficiencies with vulog :

- cntl/cmd s doesn't work on all sites, specially those that make extensive use of javascript or which have menus with high z-indices. ;)

- Highlighting - On some web page, vulog cant find the text you have highlighted. It should work on most simple sites but not on interactive ones where content is always changing. But you can always see your highlights by pressing the extension button.

- The notes and tags functionality has a bug in the current version, thanks to my clumsy fingers changing a function call name just before submitting it to the app store. But you can always take notes This is fixed in the new version.

2. Instructions

Current tab

Click on the vulog button to see the main "Current" tab, and tag a page or bookmark it using these buttons:

- The 'bookmark' and 'star are buttons for regular bookmarking.

- The 'Inbox' button is for items you want to read later. You can also right click on any web link on web pages you visit and add it to your vulog inbox right from the web page.

- Links marked with 'archive' do not show in default search results when you do a search from the Marks tab. For example, once you have read a page from your inbox, you might want to remove the 'inbox' mark, and add it to your 'archive'.

- The 'bullfrog' button makes the link public. Note that you need a CEPS compatible server to store your data and to publish it, if you want to use this feature. (See Below)

Marks tab

In the Marks tab, you can search for items you have bookmarked.

Click on the bookmark icons to filter your results. (eg clicking on inbox turns the icon green and only shows items that have been marked 'inbox'. Clicking it again will turn the button red, and you will only see items that have NOT been marked 'inbox'. You will notice that the 'archive' mark is red by default, so that archived items do not appear in the default search results.

In the marks tab, you can search for the items you have bookmarked.

When clicking on bookmark buttons, you will filter your results. (eg clicking on inbox turns the icon green and only shows items that have been marked 'inbox'. Clicking it again will turn the button red, and you will only see items that have NOT been marked as inbox. You will notice that the 'archive' mark is red by default, so that archived items do not appear in the default search results.

History tab

Search your history. The general search box searches for words used in your tags and notes and highlights, as well as meta data associated with the page.

Right Clicking on web pages

On any web page, you can right click on text you have selected to highlight it, and you can right click on a any link to add it to your inbox

Cntrl/Cmd S on web pages

When you are on any web page, you can press cntrl-S (or cmd-S for mac) and a small menu appears on the top right corner of the web page, to allow you to bookmark it. While the menu is open, pressing cntrl/cmd-I adds to inbox, cntrl/cmd-A archives, cntrl/cmd-B adds a bookmark, and pressing cntrl/cmd-S again adds a star. You can remove marks by clicking on them with your mouse. The Escape key gets rid of the menu, which disappears automatically after a few seconds in any case.

Data storage

Your bookmarks and browser history is kept in the chrome's local storage, which has limited space. After some weeks (or months depending on usage), vulog automatically deletes older items.

3. Privacy (CEPS)

vulog doesn't send any of your data to any outside servers, and you can always delete your data from the 'More' tab. If you want to store your data on your own server, you will need to set up a Personal Data Store. vulog was built to be able to accept CEPS-compatible data stores. (See here for more details on CEPS - Common End Points for Personal Servers and data stores. )

Having your data sit on your personal data store also means that you can publish your bookmarks and highlights and notes. Press the bullhorn button to publish the link from your server.

4. Future Developments

I expect to use vulog as an example app for the development of the CEPS sharing protocol.

5. Acknowledgements

Highlighting functionality was largely copied from Jérôme Parent-Lévesque. (See here.)

Rendering function (dgelements.js) was inspired by David Gilbertson (who never expected someone would be crazy enough to actually implement his idea I think.)

CEPS provides a way for applications to work with multiple data stores. For developers, this means that you can create a new app knowing that it can run on various compliant datastore systems. For Personal Data Store (PDS) system providers, it means that you can have that many more apps to offer to users of your data store. If CEPS is adopted widely, the personal data store ecosystem can only be enriched.

Today, a number of different personal data store systems are pursuing similar ends – to grant users full control over their personal data, effectively freeing them from the current web services model where third party web sites and applications are retaining all our personal data. Yet, today, each of these PDSs has its own proprietary technology and methods to allow third parties to build apps running on those data-stores.

This is a paradox that can only slow down the adoption of PDSs:

- As a user, why should I jump off the rock of current proprietary web services model to land in another hard place where apps are still proprietary (even if I get more control over my data on those PDSs.) If I am assured that I have full portability to new data stores I will have more confidence to join the ecosystem,

- As a developer, why should I build a new app that runs solely on one type of data store? If my app could easily work with any one of multiple data stores, I would be much more prone to building apps.

In this light, CEPS is the start of an effort to create some economies of scale in this nascent industry.

In its current inception, CEPS has a minimum viable set of functions to run basic apps on PDSs. It allows the app to authenticate itself on the PDS, and then write records, read and query them, and update or delete the app’s own records.

Here is how it works in practice. In the video, you see a desktop app – in this case a note taking app called Notery, but it could have also been a mobile phone app. The app connects to my PDS which is in the cloud, uses it as its store of data. Any mobile app or desktop application that you can think of could use the same model. They don’t need to send your data to some server you have no control over – using CEPS, they can store your data on your own data store.

This second clip is similar. It is an app called Tallyzoo, with which you can record and count various things. It also connects to my server and keeps data there. This is significant for two main reasons.

First, Tallyzoo wasn’t written by me. It is easy to connect some app to some server if the same person is writing both. But in this case, the app was written by Christoph from OwnYourData without any knowledge of my server. The only thing that Christoph knew was that my server would accept CEPS commands. And that’s all he needed to allow me to use Tallyzoo and store my Tallyzoo data on MY personal data store.

Second, the Tally Zoo app is a server based app – it is a web service. It is like all the great web sites we visit every day. It runs on a third party server and I am like any other user visiting a web site. The only difference is that Tallyzoo doesn’t keep my data on its own servers – it keeps the data on MY server. This is really significant in that it points to a model for all web sites to store our data on our data stores rather than on their servers.

This is a simple difference, and CEPS is a tiny little and simple specification. Yet the example above points to a world wide web which could be radically different from the one we interact with today. It shows that indeed, there is no reason for any web site – any third party company – to keep any of our data on their servers.

This may be a world worth striving for.

tl;dr: A description of the level playing field created by the personal server paradigm.

Ultimately, any for-profit entity would like to become as close to a monopoly as possible – that’s how they can charge the most for their product and make the most profit. And web services companies have all the right ingredients to become quasi-monopolies in their domain: highly scalable services, zero marginal costs, a dispersed customer base (of users and/or advertisers) who have little bargaining power, ad-supported zero-dollar-cost services, high switching costs with network effects… All of these ingredients can make web services great businesses. Ironically, just as capitalism and internet-economics reinforce companies’ monopolistic tendencies, such monopolies inevitably stifle innovation and over time, they blunt the greatest advantages of market-based capitalist economies – that is, the dynamism and innovation brought on by strong competition.

In contrast, the personal server paradigm can level the playing field, and force technology companies and service providers to continuously compete to deliver the best value proposition to end-users. In the previous post, I hinted at how that would work at the application level: Because you can easily switch apps without losing your data, you are not locked in to any particular interface or any particular company creating any particular app. Developers and companies can continuously compete to provide better interfaces to the same basic application functionality. To make an analogy to the web services model, this would be like being able to use the Snapchat app to message your friends on Facebook and retaining access to your data across both platforms.

As importantly, the personal server paradigm can also create competition for back-end infrastructure. Because you have full app-portability and data freedom, you can easily change where you host your personal server. You can of course host it on a computer sitting at home. But more likely, most people would likely host their personal servers in the cloud, using service providers like Amazon, or Google or Microsoft. The difference here is that because you can easily switch your personal server provider, they would not enjoy monopolistic control over you. So they would need to do everything they can to compete for your business and offer you better services and / or lower prices. One could imagine a Dropbox or Amazon offering this service with different prices based on the amount of data you are storing. Alas, Google might offer to host it at a lower price if you give them the right to scan your data and serve advertisements to you. And most importantly, each of these would compete to convince you that they are the most secure guardians of your data. Your privacy and control would not be driven by government mandates but by the powerful forces of competition.

This scenario is not as fanciful as it may seem at first read. Today, Amazon and Google Microsoft and others are already competing to provide cloud services to their corporate customers. And although they all try to entice their customers with special offers which locks them into their platforms, it is actually quite simple to switch.

For example, I had my personal server, salmanff.com originally hosted on Amazon – they had offered me a year for free. It took me only a few minutes to switch it over to try Google, and then a month or two later, I easily switched to Heroku. (In this case, I had kept the same data base and file servers.) In each case, my domain was also switched to the new provider and so any links I may have had (such as https://www.salmanff.com/2019-a-server-for-every-soul) would be unaffected by the move. Of course, it took some rudimentary technical knowledge to make these switches. But then again, these services are not aimed at consumers today – they are targeting developers who have the technical knowledge required. Even so, it only took some minutes for me to switch web servers and I didn’t have to use any fancy software – it was all via a point-and-click web interface. This is all the result of the more level playing field these companies face in the corporate cloud services market.

What’s more, this competition has made setting up a web server not much more complicated than setting up an account on Google or facebook. (see freezr.info) It’s all done via a web interface, and it only takes a few minutes. If anything, it has become slightly harder in the past 2-3 years to set up a freezr personal server on various services, because these services are focusing more and more on larger corporate customers, rather than amateur developers who want to set up their own servers. This is also reflected in the price tiers offered by such providers. For example, Red Hat Openshift’s trial jumps from 0 or trial usage to more than $50 per month – a jump to the high levels of usage more appropriate for corporate servers than personal servers and budgets. Clearly, if the personal server paradigm becomes popular, and many people require hosted personal servers, these same providers can easily tweak their offerings to make them even more consumer-friendly, and offer more attractive prices to them. Meanwhile, despite the fact that these companies are not targeting the (as of yet non-existent) personal server market, viable hosting solutions can be had at less than $7 per month with Heroku for example, or even potentially for free at basic usage levels. (Google Cloud recently made changes to their offering that should make it quasi free at low usage levels.)

What is amazing about competitive private markets is that they help to level the playing field – something which is markedly lacking in the technology world today. Companies like facebook and Amazon and Google have amazing technologies and amazing engineers developing their offerings. Wouldn’t it be nice if they competed to gain our loyalty without locking up our data?

tl;dr We need to be careful of the faults of decentralised systems, yet reassured by the strength of the principles underlying them. (Part of a series of posts.)

It can be instructive to compare Tim Berners Lee to Mark Zuckerberg. For example, why aren’t there any media articles holding Tim responsible for all the web sites that carry misinformation and viruses? He did invent the web that propagates all these horrors, didn’t he? Similarly, why don’t we hold the ARPANET or the US military responsible for all the email scams we receive in our inboxes? And yet we hold Mark and his company responsible for all the terrible things taking place on Facebook. Isn’t he just providing a communication utility and platform much like email and the web? Isn’t he just reaping the old reward of providing a great way for us to connect to each other using our real identities? Do we not remember the days before facebook, when it was impossible to verify identities on social networks, the days when we could not easily find nor connect to our old friends? Why should it matter that it is one company that has attracted so many users and presumably created value for them, rather than a decentralised system like the world wide web, which is based on a public communication protocol?

There are many ways to think about these questions, but I pose them here to first make the point that decentralised systems too can also be plagued by a variety of problems – identity theft, ransomware and child pornography web sites are among the dark sides of the internet.

And in many cases, the solutions to the problems plaguing open networks seem much harder to resolve than centralised ones. If we think there is an issue with Facebook or Twitter, we know that there is a company behind them that controls all the software running their web sites. We know that it is technically possible for Twitter or facebook to ban a “bad” actor from their sites if need be. So, we can shout and write nasty articles and sue them and ask Mark to “fix it, already”. But if we are outraged by a nasty web page or get caught in a phishing email, there is no one to shout at - no one person or company we can point at to solve the problem or to ban a web site. And the more decentralised and the more rigid a decentralised system may be, the harder it will be to solve the problem. This is something that any proponent of any decentralised system must be continuously wary of.

We should all be careful what we ask for.

Yet, problems on decentralised networks can also get solved, even if there is no one person we can ask to solve them. Take spam. A few years ago, it was quite common to get emails from Nigerian princes for example – a problem not totally dissimilar to the misinformation plaguing companies like Twitter and facebook today. And in this particular case of email spam, the fact that these emails are rare today seems to indicate that the participants in the decentralised email protocol succeeded in solving the problem. Yet, as pointed out to me by a very knowledgeable friend, the resolution of email spam cannot be really used as an argument in support of decentralised power structures in general –the reason this particular problem was solved is that a very few large companies dominate email services. So, as my friend pointed out, it was not the dispersion of the decentralised email protocol that drove the resolution but the power of the large oligopolies dominating the service. Although this may be true, I would argue that the concentration of players in the market is not necessarily the critical indicator here. Rather, it is underlying market structure they are operating in, and the system of governance surrounding it. Even if it was a handful of trillion-dollar behemoths that solved the email spam problem, they were on a level playing field competing to offer better services to their users and to solve such problems for them. Imagine an alternate world where Google had invented email, and that it controlled 100% of all email traffic from the get-go. Then, could we have expected Google to resolve the email problem in a new or innovative way? Isn’t it more likely that they would be entrenched in the way they had done things in the past, that they would be constrained by the business models and methods that had allowed them to dominate 100% of email traffic, and thus be blind to new ways to solve the spam problem?

Indeed, monopolies do stifle innovation.

But stifling innovation is not the only problem with monopolies - it is the values, the ethics and dynamics that are reflected in the underlying market structure and their systems of governance. It is as much a philosophical question than an economic one.

As our lives are increasingly being led online, our interactions and our data-trail are also becoming part of our Being. Our Self is reflected in, and to some extent even defined by its existence on the internet. So, it becomes even more important to think of the systems of governance we are creating through the lens of political theory.

The questions facing us now are not dissimilar to the existential dilemmas which we faced in the mid 20th century, when we grappled with the egalitarian promise of centrally planned communist economies versus the seemingly unjust and certainly unruly and messy market economies of Western democracies. It was not just that centrally planned economies stifled innovation and created inefficient economies. It was also about the structure of the system we were striving for – the values it incorporated, the rights it bestowed on citizens and the freedoms it upheld.

We can also draw analogies to the early 20th century, when Europe was still a dominant Colonial power. At the time, a pro-Colonialist might have argued that things would be much “worst” under a “native” ruler, and point to the many good things Western Civilisation had burdened to bring to the colonies. Arguably, using a measure like GDP, that assertion may well have been correct. For the sake of argument, let us assume it was - that indeed, colonialism led to higher GDP. Similarly, we can even assume that by some measures, the Colonial leadership provided more effective management, and a superior legal system for its colonised subjects. I would digress to note that an officer of the highest honesty and moral fibre within a particular world-view can be seen to commit heinous crimes from other perspectives. But even if we ignore this dissonance, even if we assume that the autocracy of Colonialism engendered an orderly system which created greater wealth for the colonised and a far better legal system, where incorruptible courts could punish and ban “bad” actors, we would still be wrong. We would still be overlooking those most valuable attributes that were of paramount importance to the colonised: their freedom and their autonomy.

So too, with data.